Go ahead = 1. better + 2. not worse

/By Duncan Anderson. To see all blogs click here.

Reading time: 7 mins

Summary

Go ahead if = 1. Better + 2. Not worse

There is always an existing solution to a problem… even if the solution is ‘nothing’. Ideally you want to make a better solution than the existing high water mark.

“It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent.” — Charlie Munger

It doesn’t matter how brilliant your idea is if it’s also filled with stupidity. AKA for your idea to be brilliant it should be devoid of stupidity.

Good idea = 1. Helpful * 2. Not Stupid (note that is a *, not plus). If our ideas unintentionally confuse people, then is it a bad idea. Don’t do that.

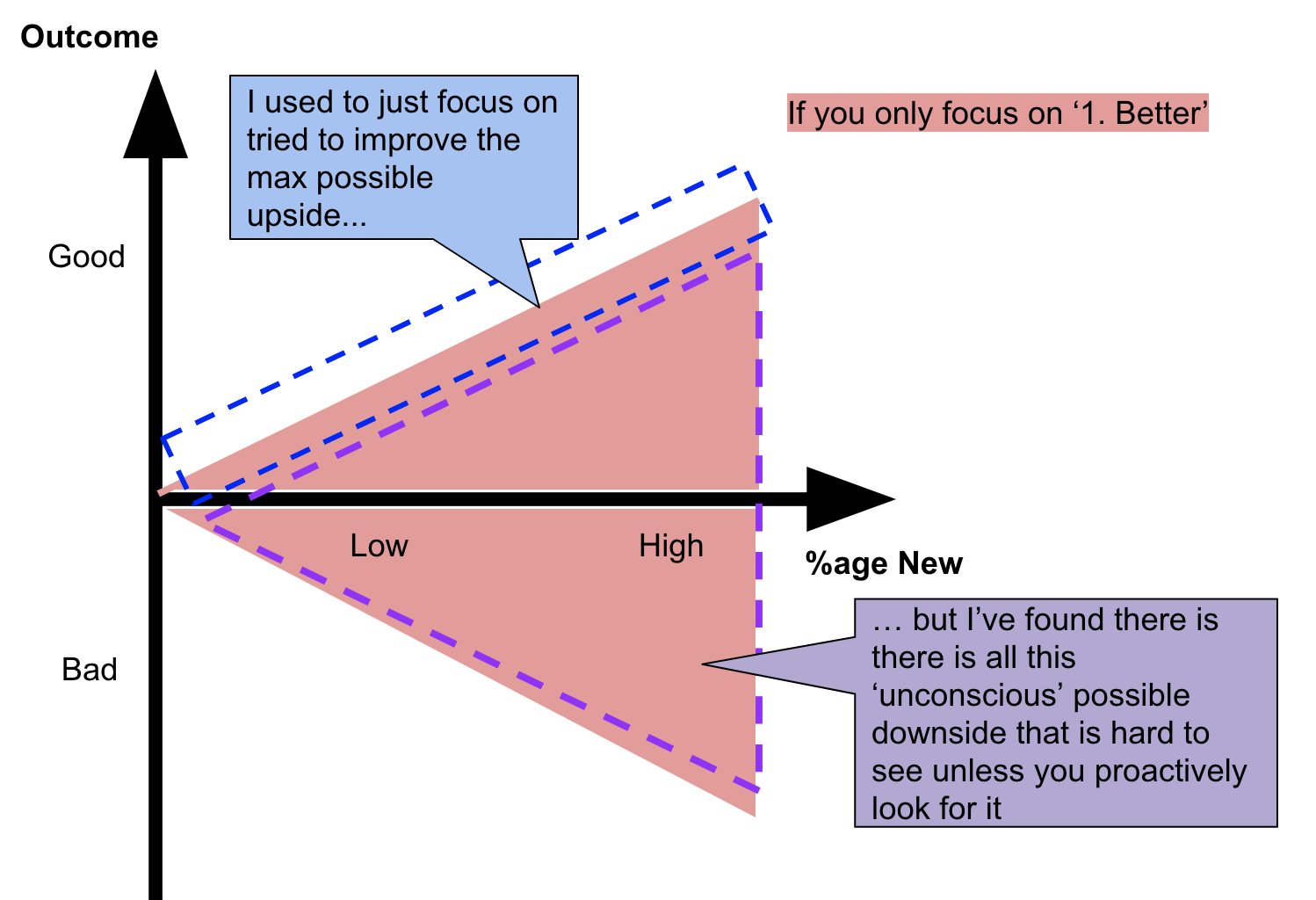

I didn’t use to think about making sure the solution wasn’t worse. I used to focus only on the proposal being ‘1. Better’. I often find it’s easy to explain why a proposal is ‘1. Better’ but hard to explain why it’s ‘2. Not worse’.

You should always be angel advocates on your idea. Think of all the ways to break your idea and why it’s bad. If you can’t think of any, then simple, it’s a good idea.

Evidence echelons - you want ‘incontrovertible evidence’ to explain why something is ‘1. Better’ + ‘2. Not worse’

L0: my thoughts

L1: some corroborating external justification - however this can easily also be confirmation bias / data mining

L2: an uncontroversial externally validatable reason why something is ‘1. Better’

L3: incontrovertible evidence - uncontroversial externally validatable reason(s) why something is ‘1. Better’ AND ‘2. Not worse’

In some respects a business is a series of accumulated decisions. Ergo, if you make quality decisions then you build an epic business.

Go ahead with proposal if it’s = 1. Better + 2. Not worse

AKA go ahead with proposal if it’s = 1. Good + 2. Not bad

See above: Good = 1. Helpful * 2. Not Stupid

Jingle: to be good, get good at explaining why you are not bad ;).

+++++++++++++++

If you are making a decision you have not made before there is a range of outcomes

“A person who never made a mistake never tried anything new.” - Einstein

When making a decision, IMO spend as much time on trying to add upside possibility as removing downside possibility.

Range of possible outcomes from the decision:

Ideally you can focus on why something is ‘2. Not worse’ until the lower bound of the range of outcomes is a net improvement. This is the best fun.

Some sample questions to ask for downside removal AKA ‘2. Not worse’ justification (in some respects this is a rearticulation of Devil’s undisqualitifed decisions)

Where could this go wrong? AKA Angel’s Advocate.

Can anyone find a hole in the logic?

For Reason A (‘variable’ if you are explaining with models / equations - link) is there another ‘counter characterisation’ of the affect?

What are we missing (eg is the Job To Be Done wrong, eg have we incorrectly MECE’d the problem space)?

What blind spots do we have? AKA is there a user persona who will view the proposal differently?

Where is my ego distorting my view of the world? AKA tell me my biases please.

User personas - you are unique... just like everyone else

One key area I’ve found to get into trouble is not understanding the different user personas and how they look at the world from different perspectives.

Levels of user base modelling - aka user persona creation

-L2: assuming that the entire user base thinks like you. Unfortunately I think this is the default for many people. Your personal experience is valid, your personal experience does not represent the entirety of all human experience. It’s likely you are not just solving a problem for yourself, so IMO think beyond yourself.

-L1: assuming the entire user base is homogenous but different to you.

L1: segment user base into 2-5x personas

L2: segment user based into 2-5x personas that cover 80%+ of the different user types and are mutually exclusive.

If I’m making a decision with a large amount of unknown (new) I try to:

Build an equation to explain the solution that has 2-5x variables and associated taxonomies.

Then I try to build the 2-5x personas for the group of people I’m trying to help.

Finally I try to explain why the proposal is ‘1. Better’ + ‘2. Not worse’ for each persona on each variable! This is normally done in a spreadsheet identifying only a few major key points. Avoid trying to identify too many variables as it muddies the data. Be specific on what each persona things is Good and what is Bad, then move on.

Different good vs Different bad - ideally you want incontrovertible evidence.

In the past I think I could explain why my proposal was different, but was it different good or different bad? I had a reason why it was 'different good', but did I have incontrovertible evidence that we are right or just 'I feel'?

Evidence echelons - you want ‘incontrovertible evidence

L0: my thoughts

L1: some corroborating external justification - however this can easily also be confirmation bias / data mining

L2: an uncontroversial externally validatable reason why something is ‘1. Better’

L3: incontrovertible evidence - uncontroversial externally validatable reasons why something is ‘1. Better’ AND ‘2. Not worse’

Comment:

With the benefit of hindsight I think that 5 years ago Duncan was often just saying why things were different… and I had some “L0: my thoughts” reasons on why that was better but frankly it was pretty weak.

Example - Year 7 Maths Questions

Let’s say you want to try and figure out how to make great maths questions for a year 7 textbook. You want these questions to be the best in the market, so as such be different to the way existing questions are done. How do you try and characterise ahead of time if your decisions are better or worse rather than existing outcomes?

This is just one component of what we are doing in Year 7 Maths.

For Year 7 Maths we systematically try to find all the misconceptions students have for each lesson and then try to custom build a learning journey (question sequence) that does not result in the misconception.

Poorly designed learning journey = misconception

Well designed learning journey = no misconception

Go ahead with incorporating misconceptions = 1. Better + 2. Not worse

1. Better = we can design a learning journey to not result in the misconception

2. Not worse = we have validated that this misconception is a common misconception (eg through academic research) and not actually something irrelevant. In the worst case scenario we would change the learning journey to ‘not build a misconception we had identified’ but 1. This wasn’t actually a misconception so not solving anything and 2. Through changing the learning journey we have an unintended 2nd order consequence of actually building a different misconception due to ‘blindness’.

Example: Leaving your job to try do a startup

When Ben, Jeremy and I started Edrolo we all committed to working on Edrolo 10 hours a week on top of our full time jobs. AKA we were moonlighting.

IMO this was ‘1. Better’ & ‘2. Not worse’ than quitting our full time jobs immediately as we had so much stuff to figure out.

‘1. Better’ = we got to learn about Edrolo and education

‘2. Not worse’ = we didn’t have cash runway issues as we still had full time jobs

Then Edrolo got some traction and we thought about quitting our full time jobs but at the time it would have meant no income as Edrolo wasn’t generating enough cash to pay us.

We found out about Startmate, similar to Y Combinator but in Australia. Startmate is a startup accelerator.

At the time I was working at Google, I realised that if Edrolo got into Startmate and then died shortly after that this would look better on my resume than ‘just staying at Google’.

So aside from having no income for eg 6-12 months if we could get Edrolo into Startmate it was actually a win for my career long term.

Edrolo applied to Startmate and got in while we all still had full time jobs, so we didn’t have to quit without knowing about this ‘safety net’.

Edrolo + Startmate:

1. Better = Get to try and make Edrolo work and if it goes well then can hopefully help improve the world and have an epic job.

2. Not worse = Edrolo got into Startmate and worst case scenario Edrolo died shortly after the end of the Startmate program = better on my resume than staying at Google = no brainer.

Example: hectic

The above two examples are pretty light on examples. If you want to see the hectic way we try to explain how entire product recipes are ‘1. Better’ + ‘2. Not worse’ you’ll need to crawl ~1000 cells in a spreadsheet and work at Edrolo!

Honestly, I find trying to do this one of the most beautiful things… but also it’s typically super dense. Duncan = dense and intense? Nonsense!

If you only take away one thing

You keep the good decisions. You stop the bad decisions.

But a bad decision can kill you. So to me it’s likely more important to try and justify why decisions are ‘2. Not worse’ / Bad than it is that they are ‘1. Better’ / Good.

To be good, get good at explaining why you are not bad ;).